How to write SOPs in life science industry?

I first saw a scientific Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) during my undergraduate training in 2003. It's been a long and winding few years since then and I have come to appreciate the value of such documentation more than ever. Back in 2003, I was just selected to spend a year as an intern in GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) as a Microbiology Quality Assurance Analyst. GSK is one of the largest multinational pharmaceutical companies in the world and I was impressed by the precise and super-efficient operations that they were running. I soon came to realize that accurate documentation and SOPs were crucial for ensuring smooth operations. Working with more experienced scientists I was taught the value of accurate record-keeping, following procedures, and ensuring data integrity.

SOPs are required by various federal and International regulations if you work in a biotech or pharmaceutical laboratory. Good Manufacturing Practices and Good Laboratory Practices, collectively know as cGxP, also necessitate the use of SOPs. But for researchers working in the lab the true value of an SOP becomes apparent when they realize better reproducibility, accountability, reporting, and troubleshooting after consistently using one.

What is an SOP?

In academic research, scientists use protocols or methods to outline the steps required to perform experiments, reproduce observations, and test their hypotheses. In this scenario, a researcher writes up the exact steps that need to be replicated in order to make an observation. Any deviations from the protocol are noted and the observations are recorded in a lab notebook. In the scientific community, protocols can be shared or published to allow other scientists to reproduce the same observations and build new hypotheses based on those observations (this is known as the scientific method). Protocols in academic research are somewhat flexible and researchers have the flexibility to change protocols to meet their own needs. For example, a scientist may decide to choose a new chemical to replace what is mentioned in the original protocol. These deviations are noted and usually published along with the new observations. This flexibility to change protocols is necessary to allow rapid discovery of new observations. Because pure academic research does not directly concern patient or product safety, the flexibility to change a protocol based on a scientist's decision is widely accepted. However, in the biotech or pharmaceutical laboratories where data and observations are used to produce consumer products like chemicals, drugs, and diagnostic kits it is important to closely monitor any change in a protocol and how it is performed. This is where standard operating procedures come in handy. SOPs are carefully drafted protocols that are reviewed, approved and version controlled. This ensures the accuracy and trustworthiness of data regardless in a setting where multiple scientists collaborate to create a product. SOPs also make it easy for the in-house and external regulatory teams to verify procedures carried out in developing products.

How to draft an SOP?

SOPs typically contain multiple sections. These include but not limited to a title, date and time of creation, version number, signatures, author details, purpose, scope, and step-by-step instructions. I found the EPA's guidance on creating SOPs a useful source and I recommend using this document as a starting point, adapting it to your needs as you see fit. Other useful resources are also linked at the bottom of this page.

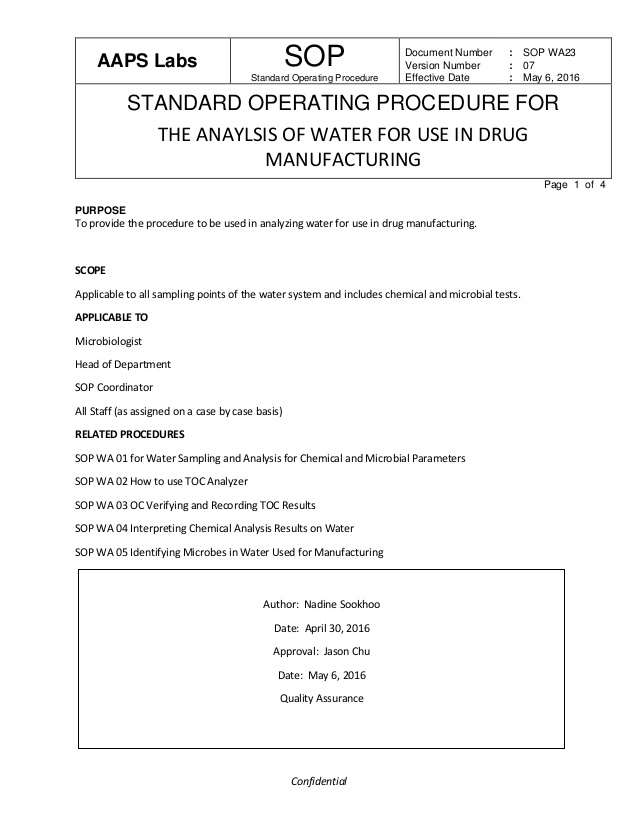

SOPs change periodically, some more often than others, so it is important to keep that in mind when drafting the first version. The header and footprint sections are useful areas for numbering, timestamps, and version control information. Drafting an SOP usually involved cross-team collaboration to ensure that everyone within the organization can clearly identify and use each SOP for the purposes of performing the procedure, auditing, troubleshooting, or identifying deficiencies in the organization's procedures. Therefore an SOP can contain multiple signatures from different departments. The image below is an example of the first page of an SOP. Notice that each section is carefully designed to serve a specific purpose.

In the above example, the header section gives you all the information you need to identify the type of the document in a quick glance. This is followed by the title of the SOP, printed in large font to allow easy sorting and retrieving from among other SOPs. Page numbering is essential to ensure the completeness of the document and the correct procedural order. Other sections on the first page, define the scope and purpose of the SOP. A scope that is too narrow results in a lot of paperwork that can hamper progress, while a scope that is too widely defined can lead to confusion and a longer learning curve for new users. It will be helpful to the users to list related SOPs that can be referred to while performing a partial SOP. The subsequent pages will include a detailed step-by-step description of the procedure that needs to be performed. Each step is numbered. If the user is expected to enter data, sufficient space must be provided to allow data recording. The user may also need to attach additional material, such as an equipment's results printouts.

The precise format of the SOP can be changed to meet specific organizational needs. It is however important to keep a consistent format for all SOPs used in an organization to minimize confusion, improve cross-team collaboration, and ensure speedy audits.

Here's a great video explaining the process of creating SOPs. Although this is not specifically geared towards scientists, this can be a useful reference.

Want to learn more about automated SOP management in your lab?

Looking into the future

It is becoming necessary for small, and medium-sized life sciences organizations to automate their operations within their cGxP frameworks. It is therefore becoming more important for companies to computerize their documents and laboratory records. Failing this, the research team would face a situation where they may be unable to deal with the expenses incurred due to audit failures, performance issues or product recalls. For a quick guide on how to create a digital workflow within the framework of relevant FDA regulations click here.

Please email us if have any feedback, suggestions, or questions about this article or to request a 1:1 walkthrough of how LabLog can help you create a robust digital workflow for SOP managing and lab data recording.

Related articles:

EPA guide for writing SOPs: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-06/documents/g6-final.pdf

Labmanager guide to writing SOPs: https://www.labmanager.com/business-management/2009/02/8-steps-to-writing-an-sop

More useful information about SOPs: https://hub.ucsf.edu/sop-guidelines

Author:

Hani Ebrahimi, Ph.D. | CEO & Co-founder at LabLog

81 - 3947253

VAT No. GB 384 5765 51.

71-75 Shelton Street,

Covent Garden, London, England, WC2H 9JQ